Okay, let's get down to the nitty gritty. Who owns the moon? Who can potentially own the moon, or resources from the moon? If this new lunar space race is really all about resources, we have to know the answer to this question, and yet there are competing interpretations of the international legal framework, the application of domestic laws, non-binding frameworks, and the potential for a simple “first come first served” regime.

And importantly, the race is not only about resources, as I discussed last week. Whoever dominates access to those resources, is likely to dominate geopolitically for the rest of the century, and possibly beyond.

(This is a particularly lengthy addition to this miniseries on “Artemis and the Moon”, hence my voiceover. Once I finish this miniseries I will write shorter newsletters that you can digest in a couple of minutes. For now, there’s just a lot to say!)

The reason I began this miniseries discussing the mythology of the goddess of the Moon, is that I consider it no mere coincidence that Artemis said to her father Zeus that she never wanted to belong to any man, and yet here we are in the 21st century debating who may own parts of the Moon that she protects and represents. We're unlikely to have a similar debate about who owns the sun, since capturing solar power doesn’t require the same proximity to the source. But as we get closer to this lunar resource competition playing out — within the next 5 years — it's likely that whatever regime gets put in place will last ongoingly, as resource extraction expands to asteroids, other planets, and whatever other resources our nascent robotics and AI might begin seeking out. So this decade could possibly have an outsized impact on the future of space governance.

A lawless frontier

If there's one thing that drives me absolutely crazy, it's the assertion that space is a wild west, a lawless frontier, that there are no restraints on commercial actors, and that it is simply a question of first come first served.

Historically, as powerful societies have sought to expand their territories and influence, they have sought to conquer new frontiers. New technologies have always provided an access to these frontiers: improved ship building, navigation and longer-range canons allowed European countries to dominate the seas for trade; trains and telegraphs enabled colonizers to expand into remote territories across land; aviation allowed access to the new “high ground” of the air.

It may be tempting to quote the opening lines of Star Trek every time we think about what’s possible in space, but inherent in the history of “conquering frontiers” are empire building, territorial claims, violence and competition — far from the stability we need in outer space if we want to continue benefitting from space-based technologies in the near and longer-term futures. And far from the truth when it comes to existing law.

There is so much law governing what we do in outer space, including civil and military governmental activities, and commercial activities. From international space treaties, to general international law, to specific bodies of international law, to domestic law.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty is the cornerstone framework treaty. You can think of it like a constitution: it lays down the organising principles, the core values, the basic agreements that States came to at the dawn of the space age. It is designed to last throughout time, and therefore to be general rather than specific. Just like national constitutions. These are not designed to regulate specific behaviours or technologies, but rather to organise a society and its governing beliefs.

When it comes to ownership, Article II of the OST strives to give Artemis her wish:

Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

Planting a flag in the Moon in 1969 was merely symbolic. All the countries in the room when the OST was being negotiated in 1967 wanted to be sure that space, the Moon, asteroids and planets would not be subject to territorial claims by the coincidentally most powerful nations of the day. Underscoring this, Article I states that the exploration and use of space shall be “for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all [hu]mankind.”

Lofty, aspirational words? Yes, but so is the text of many constitutions, seeking to guide future populations to adhere to core values.

However, the article I consider to be most important is Article III:

States […] shall carry on activities in the exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, in accordance with international law, including the Charter of the United Nations, in the interest of maintaining international peace and security and promoting international co-operation and understanding. (Emphasis added)

What this does is export whole bodies of international law to our space activities: the law on treaties, the prohibition on the use of force, the laws of armed conflict, human rights law, international environmental law. While it’s true it can be complex to figure out exactly how specific principles apply, still, that’s a lot of law!

Another important aspect of the OST is the combination of Articles VI and VII. These articles drive home that ALL activities, including commercial, have to be in accordance with this treaty and therefore with international law, and that States are responsible for ensuring this. States are also obliged to authorise and continually supervise activities under their jurisdiction.

This is what gives rise to domestic space law. Lots and lots of domestic space laws, regulations, and licencing regimes. No commercial or governmental actor can access space without gaining multiple licences and approvals — and sometimes under the legal regime of more than one State, if a launch has to be procured in a foreign country.

There are regular criticisms that the Outer Space Treaty is outdated or no longer fit for purpose, and calls to re-draft or update it. It’s about to reach its 60th anniversary in 2027, and some have suggested this would be the time to revisit it. But as I’ve argued in a piece I wrote for the Centre for International Governance Innovation, this framework treaty continues to be very successful in respect of the purposes for which it was negotiated: general principles providing hard boundaries to ensure space is not overtly weaponised, can never be claimed as sovereign territory, and must be accessible to all. Just as we don’t update or replace constitutions when new technologies or geopolitical shifts emerge, we should not think of the OST this way.

In fact, if there were attempts to renegotiate it, this would risk unravelling the very constitutional foundation that has thus far prevented competition from extending to conflict, and has ensured space continues to be seen (by the majority of the globe) as a commons. Treaties are really difficult documents to negotiate, taking years and lengthy, politicised debates about every word, comma and full stop. The text always represents a series of compromises.

At this politically supercharged point in our century, renegotiating the OST would be a really bad idea.

Rather we need to move towards new, specific regimes. Such a regime might be a treaty, but a specific one for a targeted purpose. In fact, have I got a treaty for you!

The Moon Agreement

(…granted, it lacks agreement)

Side note: A treaty can be called a convention, an agreement, a treaty - none of that changes its status as a binding “contract” between States. Carefully negotiated, any State that signs a treaty must at least act in accordance with its object and purpose, and as soon as a State ratifies a treaty into its domestic legal system, the State is fully bound by every word of the text. In fact, there’s even a treaty that explains the law of treaties, which international law nerds like me love.

By 1979, it was already clear that some States dominated in space, and that a future competition over real estate and resources in space might take place. In order to pre-empt this, a small group of countries decided that Article II of the OST needed further clarification, and they negotiated the Moon Agreement.

Whereas the OST uses the rather vague term “province of [hu]mankind”, the Moon Agreement went a step further, stating that space, the Moon, and all celestial bodies (i.e. naturally occurring bodies like planets, stars, asteroids etc) are the “common heritage of [hu]mankind”. The term “global commons” isn’t a legal term, but the common heritage principle is often what people are referring to when they say “global commons”.

Joanne Gabrynowicz wrote an important piece about the difference between “province” relating to our activities in space, and “common heritage” relating to space itself, which is worth a read.

Importantly, article 11(3) is adamant that Artemis shall get her wish:

Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non- governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person. The placement of personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations on or below the surface of the moon, including structures connected with its surface or subsurface, shall not create a right of ownership over the surface or the subsurface of the moon or any areas thereof.

No ownership. Of any part of her. By anyone. Not even of resources that might be extracted. Full stop.

However, in the realistic anticipation that resource extraction is likely to take place some time, section 5 of the same article obliges States that have signed the Moon Agreement to come up with a regime to govern those activities “as such exploitation is about to become feasible”.

That’s now!

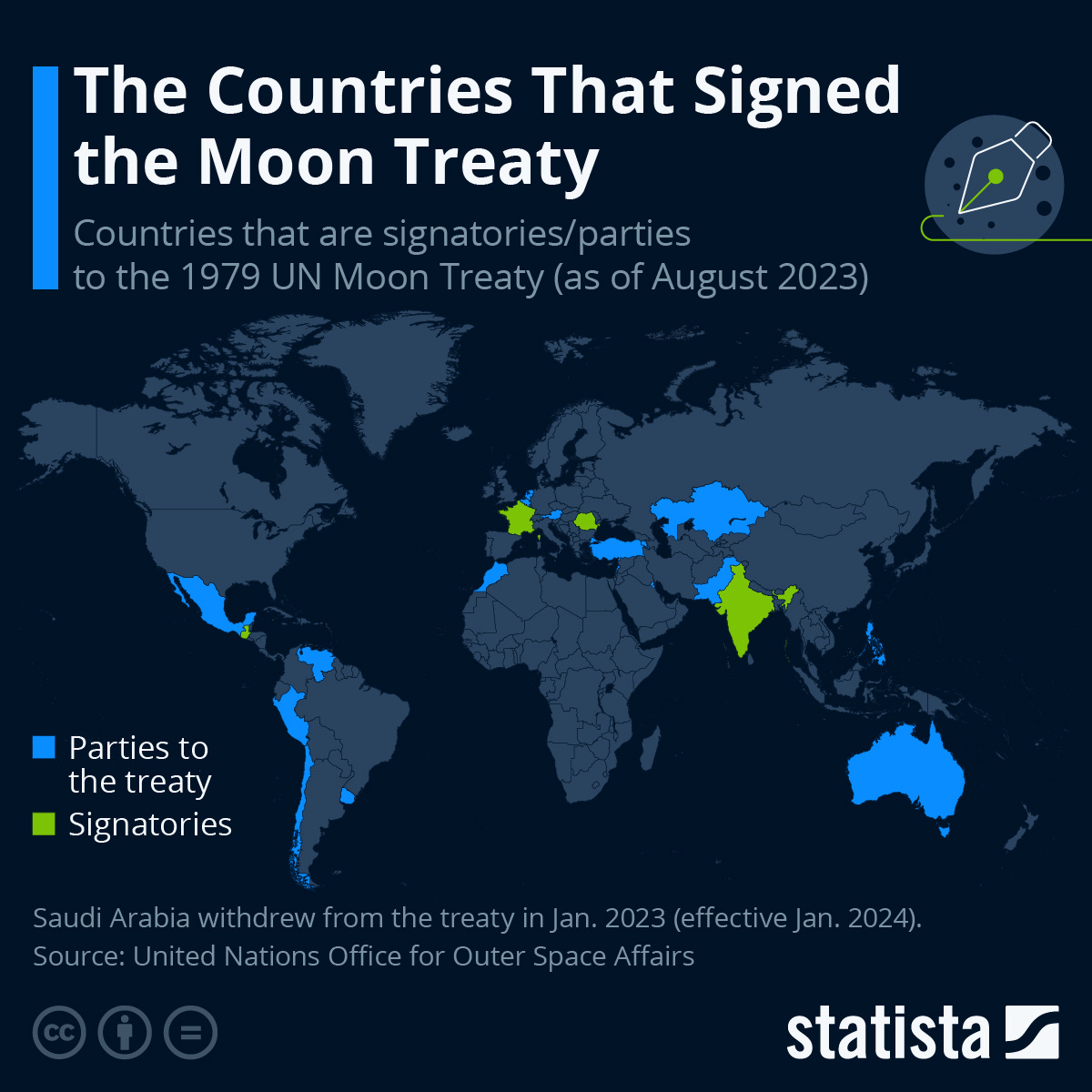

So why aren’t we jumping for joy around the world that this is about to be resolved? Because only 17 countries have signed this treaty. None of the major space powers have signed it, and the U.S. has been very explicit that it never will, and that it does not consider any part of the treaty to be “customary international law” (a source of law that applies even to countries that haven’t signed it, because it’s become accepted law. This is generally the status given to the OST).

Why is it that the major players want no part in this treaty? Because section 7 of Article 11 says that this regime has to include “[a]n equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from those resources”, with special consideration for developing countries.

The big players don’t want to be forced to share those benefits. Because they know that the ability to access these resources will set them up as ongoingly dominant players, economically, technologically and politically. Why would they give this up?

Some will try to argue that the Moon Agreement is therefore a “failed” treaty. But it’s still a valid, binding treaty on the States that have signed it. Small treaties aren’t failed regimes, though they may be limited in their global impact. But there is something overlooked about the countries that have signed, and the potential weight they could have if they used this to push forward some of the other, larger multilateral efforts taking place which I’ll talk about next week.

The 17 signatories include some Western nations like Australia, Austria, Belgium, France, the Netherlands. While France is a very important player in space, none of these are dominant players. But they are extremely important middle powers, with shared strategic interests in the new global order that’s emerging right now. It also includes some super important Indo-Pacific nations like India, Pakistan and the Philippines. And it includes several key Central and South American nations. That’s not nothing.

In fact, in a new age where middle powers and regional blocks of countries can make an extremely large impact if they work together, this collection of countries could really do a lot.

The Artemis Accords don’t accord with Artemis

When the Artemis programme was announced in 2019, it was, as I discussed last week, intended to be an internationally collaborative mission to return to the Moon. It therefore required a clear framework for operations, and a clear statement on the legal approach to resource extraction.

Already in 2015, the U.S. had adopted a piece of legislation which made very clear that it would pursue resource extraction, and that it would interpret Article II of the OST as allowing these activities. The Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act was the result of some effective lobbying on the part of start-up companies which saw a opportunity in asteroid mining, and wanted clarity that their property rights would be protected. The Act states that any U.S. citizen — which includes U.S. registered companies — shall be entitled to:

“possess, own, transport, use, and sell (any) asteroid resource or space resource obtained in accordance with applicable law, including the international obligations of the United States”

The next paragraph clarifies that the U.S. interprets its international obligations under the OST as permissive of this legislation, stating “the United States does not thereby assert sovereignty or sovereign or exclusive rights or jurisdiction over, or the ownership of, any celestial body.”

Still, citizens and companies can possess, own, transport, use and sell those resources.

This was highly contentious at the time, debated by international lawyers around the world. But it was not challenged.

Indeed, Luxemburg and the United Arab Emirates followed suit in adopting legislation asserting such property rights are not an expression of sovereignty, and are permissible under the OST. In fact, those two countries went further and offered to protect the property rights of any foreign company with a subsidiary or an HQ in their territory, to attract foreign investment and perhaps to increase the position of these two countries in the future.

Then, in 2020, NASA announced the Artemis Accords, a document intended as a basic framework for inviting countries to become partners in the Artemis programme. Of course, with the requirement that they would agree to this interpretation. It began as a series of bi-lateral agreements with each of the seven original signatories, all partner nations very keen to seal their role in Artemis. They were invited to discuss final wording behind closed doors. I have been told that there were some very minor tweaks agreed on before the document was released publicly, but that the text was asserted as pretty much final. A unilaterally drafted document asserting a very key interpretation for the future of space power and the space economy.

And a binary choice: agree, or you can’t be part of Artemis.

Over the last five years, the nature of the document has morphed. I’ve spoken at length with Gabriel Swiney, the State Department attorney who was one of the lead authors of the Artemis Accords, and who I respect enormously, though our views on the Accords diverge significantly. He agrees the document now has a life of its own. As of May 2025, 55 countries have signed it, however many of them may never contribute to Artemis, nor do they necessarily sign it with the intention to do so. No longer a bi-lateral agreement with the U.S, it has become an expression of alignment, since the major competing lunar programme is the Sino-Russian collaboration, the International Lunar Research Station. Countries are expressing which side of history they wish to be on.

It seems the Moon Agreement, which respects Artemis’ wishes, and the Artemis Accords, which don’t, are in stark disagreement. Yet Australia, France, India, Mexico, the Netherlands and Romania have signed both. Saudi Arabia had signed both, but momentously, in 2023 it withdrew it’s signature from the Moon Agreement — an extremely rare occurrence in international law. It did so to give preference to the Artemis Accords, a non-binding, political document.

You can read a fantastic analysis of the consequences of Saudi Arabia’s withdrawal here, by Jack Wright Nelson and Stefan-Michael Wedenig.

It seems we are rapidly moving towards a politically preferred regime that is about supporting the dominance of the usual suspects, rather than one that will ensure continued access for everyone. Indeed, in 2020, President Trump included in one of his Executive Orders the statement that the U.S. does not consider space to be a global commons.

Space resources may be a fantastic contribution to the 21st century. But we therefore need to determine together whether extractivism will prevail, or some form of benefit sharing, no matter how basic.

So, who owns the Moon…?

Everyone does. As a subset of which, you and I do. And therefore no single entity can own it, or any part of it, to the exclusion of others.

But given that resource extraction is an imminent activity, it is still not yet clear exactly what the applicable legal regime is.

Perhaps a legal regime isn’t the answer, then. The law is only one tool to govern people, places and activities, and it’s sometimes an inefficient one. Slow to react to new technologies, difficult to determine language that defines things adequately, and on the international plane, extremely difficult to gain the necessary and sufficient level of consensus, or even agreement.

Perhaps other efforts at non-binding agreements and guidelines and best practices are the best way forward. These are what I’ll look at next week in Part 4. But then, who is defining these, and what are the interests driving States to adopt one version over another?

Time is short, and a civil society of space citizens doesn’t have much of a window to influence the outcomes. But we can influence who gets to have a say in it. Space governance must be multistakeholder, participatory, and must absolutely include intergenerational commitments. It is simply unacceptable that short-term political or commercial interests determine the mechanisms, regimes and practices that will last into the future.

Next week, in my final installment of this miniseries, I promise to be shorter, as I discuss why I think we should all be making a bit more noise about all of this, and give some examples of space citzenry in action.

Thank you for reading (or listening) this far. And please feel free to share with anyone you want to inflict my rants upon.

I didn’t realise Australia had signed both the Moon Agreement and the Artemis Accords. It makes me wonder where we currently stand. I hope our leadership chooses to uphold principles of equity and cooperation. I really appreciate these longer pieces and thank you for taking the time to write them.

Also thank you for the links to extra reading material!