Can you buy the Moon?

You can - if you believe "Mr Hope"

World space week kicked off on October 4th, and what better way to celebrate than buy yourself a piece of the Moon. Did you know you can buy a piece of lunar real estate for just $34.99 USD? And you can even choose which location, from views over historical Moon landing sites — including the recent landing site of India’s Chandrayaan-3 on the lunar south pole — to highly sought-after scientific sites.

Maybe you want to step out in Style with one of our Location, Location, Location Series? We have Chandrayaan-3 and Apollo 15 view lots, Sea of Tranquility and Moon Rabbit to choose from as well.

- Lunar Embassy

Imagine being able to pass on this legacy to your children and grandchildren. Don’t miss out, the lunar gold rush is upon us! Step right up, ladies and gentlemen, to buy a ticket to lunar history, where you, too can make a scam artist rich by paying him for a piece of paper complete with letterhead from his made-up Lunar Embassy and come out with precisely nothing more than a good story.

Maybe scam artist is too rough a term. Dennis Hope, founder of Lunar Embassy, seems to truly believe he has a legal claim to the Moon. He thinks the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits appropriation in outer space, only applies to countries, and he once wrote a letter to the UN staking a claim over the Moon. Since he never heard back, he assumes his claim is legal. (I mean, have you ever tried writing a letter “Dear United Nations…” and assumed it will land on the desk of, well, anyone? Especially if what you have written is complete legal nonsense?)

Indeed, there are a couple of companies claiming to be the only legitimate place you can purchase bits of the Moon, and I think they’re probably all convinced that what they’re selling is real property rights. But they have it very, very wrong, I’m sorry to say to anyone who has handed over money and believed the declarations and maps they have received in return are actual deeds. They literally aren’t worth the postage you paid for them.

It’s giggle worthy, and always good teaching material in a space law class. But the thing is, it’s not far off from the promise being made that there is a market for lunar resources here on Earth, on the basis of which sales are already being made, even before any such resources have been identified or extracted. And not for $34.99. For millions of dollars.

A Lunar Economy Coming to a Space Near You

A recent news article was sent to me by a friend who told me “dude, they’re already mining the Moon!” I reassured them that nobody has yet managed to do so, but this article suggests (misleadingly) otherwise. The article highlights a recent contract between a Finnish company that provides cryogenic cooling that is necessary for quantum computing, and an American space company:

[Finnish company] Bluefors, a leader in cryogenic cooling systems, will purchase up to 10,000 liters of helium-3 annually from [US company] Interlune, with deliveries scheduled to begin in 2028 and continue through 2037….“sourcing abundant Helium-3 from the Moon helps Bluefors build cooling technologies that will unlock the potential of quantum computing even further.” - from Hot Hardware, “Quantum Computing’s Next Frontier Is Mining For Helium-3 On The Moon”, by Aaron Leong

What’s crazy about this, is that goods have been promised, money has been promised, and nobody knows with 100% certainty whether Helium 3 can be extracted from the Moon, nor how it can be processed and safely shipped back to Earth, nor at what cost.

No any entity has yet successfully extracted ANY resource from the Moon. Let alone shipped it back to Earth!!!

This is a really important quote from that article:

“In the meantime, Interlune has been busy developing the technology to harvest such resource…and process it for transport back to Earth.”

BUSY DEVELOPING!!! They haven’t even got the technology in place in a test lab here on Earth. And once they do, who knows if they can get that mining technology to the Moon to test it in situ? India has recently successfully landed on the South pole, but others have crash landed, including an Israeli company, a Japanese company and a US company, meaning their equipment didn’t survive or at least couldn’t do anything once it landed. Even national programmes are in experimental mode, including NASA which, despite several successful Moon landings under the Apollo programme in the late 1960s and early 70s, now has a shifting, uncertain timeline for Artemis and unclear core launch technologies.

The world is still in learning phases to GET back to the Moon, let alone mine it. Once there, lunar regolith is extremely fine dust that, if it gets into machinery, can prevent it from working or degrade it entirely. We’re in baby steps here. Nobody knows exactly where to extract things, if they can extract it, whether they can extract enough.

And then we need new rocket and capsule technologies that can return these things from the Moon to Earth. That’s a whole different ballgame from mining, and presumably different entities will be providing this service, with their own price tags.

Yet Interlune is signing contracts to do this all by 2028. Even if they manage it, how much will all of this cost??

This is not to say none of it is feasible. It is very likely that we will see some form of lunar mining by the end of this decade. Within the next 5 years. But the numbers don’t add up. The exchange of contracts promising goods and services that don’t yet exist is a little bit entrepreneurial snake oil salesmanship.

It doesn’t help that we have this total and utter nonsense circulating YouTube-iverse (just watch the first 2 minutes of this 6 minute clip, in which retired Air Force Lt General Steven Kwast talks about how easy it ease to manipulate truth, and then, with no irony, makes an outright bullshit claim that China is already mining the Moon for Helium-3 and has enough energy to power the world for thousands of years):

Let’s be really clear. There IS a race to locate and occupy prime real estate on the Moon, including sites where it is LIKELY that Helium 3 or ice or other potential resources MIGHT BE extractable. But nobody is doing it yet! Nobody has won this real estate race, let alone the supposed resource race.

Moreover, the economics of this is all made up at the moment. Some claim it’s a quadrillion dollar industry. Yes, they really use that figure. But based on what?

Round and Round the Merry-Go-Round

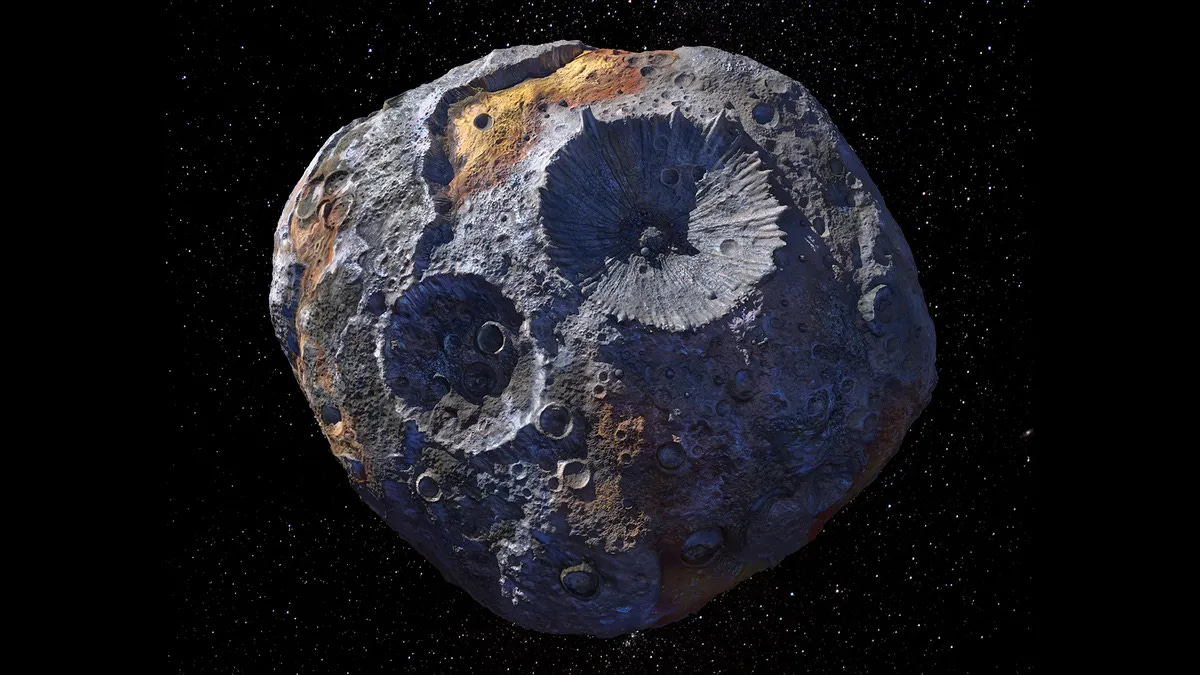

Back in the late ‘noughties and early 2010s, a number of (mostly American) companies were making the case that extracting resources from asteroids would be the panacea for any Earthly shortage of critical minerals and other finite energy sources. Planetary Resources, which had backing from Google, and Deepspace Industries, were examples of venture-backed companies which claimed trillions of dollars of value could be extracted from asteroids and returned to Earth. At a cost of over $2 billion per individual mission, to be sure.

These companies had mixed narratives: it was about filling the resource gap on Earth, but also about supporting deep-space exploration through providing water, minerals and fuel sources in space, but also about US dominance in a near-Earth economy, but also about humanity’s desire to explore and discover extra-terrestrial life, but also there are technologies that astronomers could use, but also …. reminds me a bit of those crazy mirrors at the carnival, that shape-shift you from being tall and skinny to short and fat, to upside down. It can’t be all these things at once, but if we just change perspective, maybe we can sell it to some new venture capitalist.

Tellingly: neither company exists today. They were both acquired by larger companies and have since disappeared altogether. Because what they were selling wasn’t feasible, didn’t add up, and it wasn’t even clear what these expensive dream missions were trying to solve.

Yet we still hear the same mixed up stories being sold today, claiming there is $100,000 quadrillion of value to be extracted from a single asteroid (yes, an actual figure cited), even though the it’s “economically dubious” to bring these minerals back to Earth (and that’s a direct quote!), and even though those minerals are declining in value on Earth.

As those companies and their attempts to sell us asteroids faded away, they were replaced by a new focus on the Moon by the mid-2010s. We are now well in to a geopolitical and commercial race back to our natural satellite. Again, the narrative for why, though, is very mixed. Both unclear and circular.

The main narrative is that resources will be needed to support long-term human habitation on the Moon, but that long-term human habitation is only necessary in order to access and use resources.

It’s about humanity’s return to the Moon, together, united. But also the US wants dominance and fears China.

And it’s about Sino-Russian collaboration, except China seems to be moving along fine without Russia.

And also NASA’s Artemis is about putting the first woman and first person of colour on the Moon. Except it no longer is, under an administration that makes clear it is erasing any gender or race “ideology”.

Oh and it’s about the Moon being a stepping stone to Mars. But actually it’s about long-term human presence on the Moon.

Except it’s about robotics rather than human astronauts.

And it’s about finding resources to supplement Earth’s finite resources. But actually these resources will be used in-situ.

Some narratives are simply about “next steps” for humanity, without a clear end-goal of any kind at all. An attempt to plug in to an assumed inspiration to know whether we are alone in the universe.

To be clear, the ROI on all of this is political, not economic. It is a geopolitical race for dominance over something that is likely to have value, even if this value has not yet been clearly identified.

But even if there were a real market for it (there might be! But the actual market has yet to be identified), are these companies not trying to sell the very same thing Mr Hope has been selling to anyone and everyone willing to pay him? What’s their claim over these lunar resources? What’s the difference if a country says a company can do it, versus Mr Hope just selling it on his own?

What Does the Outer Space Treaty Say?

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty is the cornerstone of international space law. It’s true it was negotiated and written by States, and that in general international law is about States agreeing to be bound to act a certain way. But this doesn’t mean there’s a “loophole” that would allow individuals to act against the intention of the treaty. Human rights treaties bind States, but that doesn’t mean I can just go and torture someone and say I’m not bound by international law. When there’s a trade treaty between two countries, it doesn’t mean an individual or a company can go outside what is agreed and just do what they want. When a treaty says there is no “national appropriation” in outer space, “by claims of sovereignty, nor by any other means”, which is Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, that doesn’t leave it open to an individual to say “yeah, but I can appropriate the Moon, because I’m not a State”.

In fact, international law lives in domestic law: the application of international law obligations and rights are more often than not expressed in the legislation which States put into place within their own borders. That’s how we know if they are adhering to treaties. Sometimes it’s about what they are doing outside their own borders, but it almost always requires some domestic laws to activate the treaty at a national level, and then often requires even more specific legislation to fulfill on exactly what the treaty requires the State to do.

Without wanting to get too technical:

a State binds itself under international law when it signs a treaty;

then, most States require some kind of implementation at the domestic level, like a law of adoption (thought some States, like the Netherlands, have a “monist” approach that says as soon as the treaty is signed, it becomes Dutch law);

but even if a State fails to “ratify” in this way, their signature still binds them to act in accordance with the object and purpose of the treaty (i.e. it’s general intention, even if the specifics of each article may not bind the State. In the case of the Outer Space Treaty, the prohibition on appropriation falls under it’s object and purpose);

after ratifying, in some cases, a State would also have to adopt some specific legislation to answer it’s obligations under specific articles of the treaty. An example would be if a trade treaty between two countries requires a limit on tariffs (you know, those things that add an extra tax at the border when something is imported, where the cost then gets passed on to the customer in that importing country? Yeah, those things). Each State that has ratified the treaty would now have to put in place some domestic legislation about capping that tariff for goods imported from the other State.

So, the US, where Mr Hope lives, has both signed and ratified the Outer Space Treaty, meaning it is US law. Now no US entity can do anything that is in breach of that treaty, or the US will be responsible under international law. There are all sorts of rules of interpretation about State responsibility, but if any doubt remains as to whether Mr Hope, or any of his unfortunate clients, can actually own or buy a piece of the Moon when the US is bound by the prohibition, the Outer Space Treaty removes this doubt for us. The US and all other negotiating States back in 1967 took care of this in Articles VI and VII.

Those articles say that the State remains responsible under international law for all national space activities, whether “governmental or non-governmental”. Whether NASA, or SpaceX, or Mr Hope. They also place an obligation on the State to “authorize and continually supervise” those activities: in other words, to put in place domestic licencing and other regulations. It’s up to the State how it does this, but the State is fully responsible. Individuals and companies can’t do something without being told by the State that they can, and they can’t do anything that would be in breach of the the treaty. If they do, it either has no legal effect, like Mr Hope’s deeds to the Moon, or — if there is damage caused by these activities — the legal effects would be that the State becomes responsible, and is likely to seek damages or recompense from the person or company who caused the harm, under its own domestic laws.

Too legalese? My point is, Mr Hope’s claim is nonsense. There’s no “loophole” for an individual or a company to claim ownership of the Moon and sell it to you.

What About Domestic Laws?

OK, but some States have enacted domestic legislation that welcomes companies which might want to extract space resources and sell them. And we have the Artemis Accords, now signed by 56 countries, which state very clearly that lunar resource extraction is lawful under the Outer Space Treaty. Isn’t this all the same as Mr Hope?

I gave examples of these domestic laws, which assert space resource extraction is not in breach of the Outer Space Treaty, in my earlier newsletter “Artemis and the Moon Part 3” . (That was part of a miniseries where I dove into the mythology of Artemis, goddess of the Moon, and how the legal, political and commercial race for lunar dominance flies in the face of this mythology). From that newsletter post:

The 2015 Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act enacted by the U.S. was the result of some effective lobbying on the part of start-up companies which saw a opportunity in asteroid mining, and wanted clarity that their property rights would be protected. The Act states that any U.S. citizen — which includes U.S. registered companies — shall be entitled to:

“possess, own, transport, use, and sell (any) asteroid resource or space resource obtained in accordance with applicable law, including the international obligations of the United States.”

The next paragraph of the law clarifies that the U.S. interprets its international obligations under the OST as permissive of this legislation, stating “the United States does not thereby assert sovereignty or sovereign or exclusive rights or jurisdiction over, or the ownership of, any celestial body.”

Still, citizens and companies can possess, own, transport, use and sell those resources.

This was highly contentious at the time, debated by international lawyers around the world. But it was not challenged.

Indeed, Luxemburg and the United Arab Emirates followed suit in adopting legislation asserting such property rights are not an expression of sovereignty, and are permissible under the OST. In fact, those two countries went further and offered to protect the property rights of any foreign company with a subsidiary or an HQ in their territory, to attract foreign investment and perhaps to increase the political position of these two countries in the future.

These States are all saying “we know the Outer Space Treaty says no national appropriation. We just don’t think this would amount to appropriation.” They are waging a bet that they will progress with these activities without any meaningful international pushback, and it will become an accepted interpretation of the treaty.

This is how treaty interpretation usually goes when there are contentions. States assert that the thing they want to do is, in fact, in accordance with a treaty. They test it out with political statements and see if there is pushback. They put in place domestic legislation, and they start acting a certain way to establish State practice. And it either becomes accepted, or is contested.

If another State considers itself to suffer some kind of injury because of this, it can contest what the first State is doing, push back politically, and eventually, if the injured State wants to litigate, it can bring a case before the International Court of Justice. The UN court, whose job it is to determine international law, with the intention of peaceful resolution. It’s job is literally to avoid wars as the go-to resolution of disputes.

But if it’s a treaty that isn’t about a specific relationship between two States, or if there isn’t a direct injury to a specific State — unlike, say, a trade treaty, a border agreement, or an environmental law treaty — then it could be a treaty obligation that is “erga omnes”. A fancy Latin term to mean “obligation with respect to everyone”. Like the Convention Against Torture, the Antarctic Treaty System that prevents any new claims of territory in Antarctica, or the Paris Climate Agreement which requires States to set nationally determined CO2 contributions.

The Outer Space Treaty is about the organising principles and legal obligations on all States and all actors in space, literally “for the benefit of all” humankind, as stated in Article I. The prohibition on national appropriation in Article II is therefore “erga omnes”, an obligation with respect to everyone.

So, in theory, any State that believed these domestic laws were in breach of the Outer Space Treaty could bring a case to the International Court of Justice, and the court would have to decide on their legality.

The weakest link in international law, however, is political will. No country right now feels that the political cost of bringing the US, the UAE and Luxembourg before the UN International Court of Justice would be worth it. Litigation is peaceful, but it can be very antagonistic in international relations. There’s also the question whether the losing State will respect the Court’s decision, even though all countries are supposed to. The US has a long and consistent history of ignoring findings by the UN Court against it, or arguing that it can’t do anything about a breach because it’s states rather than federal government who have legislated. Anything to get out of legal obligations they disagree with.

(Sorry to my American friends, but it’s simply a fact that the US has been a defending litigant before the court more than any other country, and has more often than not chosen to ignore findings against it. This is why I’m not so worried about the precious “international legal order” fading away right now. It was a bit of smoke and mirrors while it lasted anyway. I am a firm believer in international law, but I am also clear that rules alone are not enough. There has to be a shared willingness to follow those rules, and they therefore need to be written by more actors than just the victors of the Second World War. But that’s another story…)

Right now, we can pretty safely assume that the current US administration would give precisely zero heed to a UN court, and would double down on aggressive tactics against any nation bringing it before the court. The UAE does some international law cherry picking as well, particularly around human rights. And while Luxembourg is a small country, it is making the bet that if the US can get away with it, there’s nothing to stop other countries from doing the same.

Snake Oil and Lunar Real Estate

Is all of this really different from Mr Hope’s claim to own and be able to sell the Moon?

In some small way, yes. International law is the express will by States to be bound by rules and norms. Other actors can form international law, like international organisations, and civil society, and even judges and lawyers, but it mostly comes down to shaping and restraining State behaviour, based on State agreement. Some rules are explicit and clear and “hard”, others are less so. And some change over time, through something known as “subsequent interpretation” and new State practice, as long as other States have somehow accepted those changes through their own statements and actions. But an individual just making a claim that he owns the Moon (or Antarctica, or some area of the high seas) has no legal basis. Otherwise there is no legal order at all. There’s just a bunch of assertions.

There’s a lot of critical international law theory which debates whether that’s all international law is between States, a bunch of assertions. And debates what happens when there is consistent flagrant breach of important rules. Some will debate whether lack of enforcement means there is no legal order at all. Some will say there is certainly an international legal order, but that there is an increasingly larger group of actors able to shape it.

The point is, practice will determine how we collectively agree off-world resources are to be governed. Whichever country, or company, or collaborative collection of countries, manages to be among the first to successfully extract resources, will set the tone around what follows — depending on how others respond. This is why collaborative efforts like ATLAC (the multilateral Action Team on Lunar Activities Consultation, which is attempting to bridge divides in UN discussions) and Open Lunar (a civil society effort) are so important, as I wrote in Artemis and the Moon Part 4.

So in other ways, it’s not really so different from Mr Hope’s claim to the Moon. It’s just about who has the power to determine the rules.

What’s more, the Moon is a testing ground. The 1967 Outer Space treaty (and all the other space treaties) talk about “the Moon and other celestial bodies”, meaning all natural bodies in space. Asteroids, planets, dwarf planets, comets, stars, all of it. The Moon gets singled out because it was the focal point of the 1960s space race, and it is certainly the focal point of this 2020s space race. But the point of that treaty language is to set the ground rules (space rules!) for all extra-terrestrial bodies. No national appropriation. No extra-terrestrial land grabs. Natural bodies in space can’t belong to any nation, any entity, there is a right of exploration and use for all countries, and space activities shall be for the benefit of all humankind.

Also, it’s pretty fricking egotistical to think any of us could claim what’s out there, and just assume what we want to extract from it is worth more than its intrinsic value. Or maybe even its value to other beings.

But those more philosophical questions aside: with these domestic laws, with the current international and commercial race to secure prime lunar real estate, what happens on and around the Moon will determine what happens throughout space and time, for the rest of this century. And most likely beyond. So we should probably give it a bit more attention, and look behind the smoke and mirrors.