How space is used in war

(Or "How space can help make war on Earth suck just a little bit less")

My interest in space security and space law grew out of my research background in the laws of armed conflict and international criminal law — the prosecution of individuals for mass atrocities like genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The worst expression of humanity in situations where the moral compass has been turned upside down. After completing my PhD, and having taught international law and criminal law for nearly a decade, I began to take an interest in how technology was impacting the issues I focused on. Not because “technology and warfare” were new concepts, but because there were technologies I didn’t understand in the early 2000s and 2010s, which were making it increasingly difficult to answer questions of liability and responsibility.

Drones, cyber attacks, and space capabilities were what my military lawyer colleagues were most interested in, and they were challenging the frameworks I applied to atrocity and warfare. Sometimes in good ways, by increasing precision of attacks and reducing human loss. Sometimes in bad ways, by doing precisely the opposite.

I found drones too horrific, and cyber too complex, and so followed the advice of some military lawyer friends to turn to space. Their advice was not because it was new, but because it was neglected by international lawyers.

Since humans first accessed space in 1957, militaries have used space. Satellites have been key to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, and to military communications from the get-go. And while the Outer Space Treaty was very much an instrument designed to prevent the Cold War competition between the Soviets and Americans from projecting into space, nevertheless space-based technologies have changed the character of war for decades, and are likely to play an even greater role in decades to come.

So how is space used in war? Strap in, some images below might be uncomfortable.

Space and the character of war

Anyone who has studied conflict, security or peace studies will be familiar with Clauzewits’ theory that the nature of war remains constant throughout time: war is a clash of wills, violent, interactive, and political. Yet he also stated that the character of war changes: politically, socially and economically, wars can be very different over time. Technology has always impacted how wars are fought: moving combatants further away from each other with the invention of guns and canons, allowing empires to expand across oceans with armed naval ships, and providing greater intelligence from the air and greater destruction from above with aircraft bombers. The character of war may not have changed immediately with the opening up of the space domain to human technologies in the late 1950s, but space has certainly become a critical domain to warfare in the decades since.

When the Soviets launched Sputnik in 1957, there were media frenzies in the West speculating whether this was a weapon, or a sophisticated intelligence-gathering technology. In reality, it could only emit a simple signal that allowed its orbit to be tracked, but within just a few years both the U.S. and the USSR had launched several satellites to provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) from this new “high ground”. In particular this meant they could monitor each other’s nuclear tests and programmes.

Communications satellites were also very quickly part of both military and commercial space infrastructure. Already in 1966, the first military communications satellites were launched, and while the first Satphones were really big, heavy bits of equipment, they allowed troops on the ground to communicate during battle.

And that thing you and I use for free to find our way to a cafe with our smartphones, or to track our cycling and running routes on our smartwatches? The Global Positioning System (GPS) was a U.S. military satellite technology first launched in 1978. Early testing required soldiers to wear the very gender specific “manpack”, a hefty backpack receiver weighing about 8kg, and to carry a handheld device for the visual positioning. Can’t imagine seeing anyone jogging or cycling with that outfit, but access to real-time satellite signals was a game changer for navigation on the ground, at sea and later, in the air.

GPS was made available to civilians in the 1980s, and was fully operational by 1995. But unless you had a high end Garmin-like device for orienteering or mountain climbing, you probably weren’t using it until the early 2000s, when “satnavs” became a thing we pulled out for long car or motorbike journeys, and packed away in their cases when unused.

My comments here are mostly about GPS. The Russian GLONASS system was launched and became operational on a similar timeline as the GPS. The Chinese Beidou system was a bit later, in the early 2000s, and the European system Galileo didn’t come online until 2016.

The first “space war”: Operation Desert Storm

Recreational use aside, GPS drastically changed the character of war in the 1990s.

The U.S.-led allied “Operation Desert Storm” in Kuwait and Iraq in 1991 was a swift operation, lasting just a few days, and proving key in dismantling Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. It is often referred to as the first “space war”, not because the war extended into space, but because space was very present on the terrestrial battlefield.

Satellite capabilities provided an unprecedented advantage to the U.S., in particular GPS. Although it was only made up of 16 satellites at the time, leading to some gaps in connectivity (at the mid-earth orbital altitude of about 20,000km, it requires at least 23 satellites in order to have 24 hour coverage), portable access to GPS signals made navigation in the desert possible for foreign troops unfamiliar with this challenging landscape. Indeed, it gave them access to parts of the desert that locals didn’t go very often. Accuracy was at about 16 metres, compared to today’s civilian access of two metres, and military grade accuracy of a few centimetres. Portable receivers were expensive (tens of thousands of dollars), and in short supply, so commercial providers were hastily contracted, and some soldiers were asked family members to send them run of the mill satnavs from home - which were still a couple of thousand dollars each, but easy to buy.

It also made it possible to target moving tanks and artillery with far greater precision than ever before. GPS-guided weapons were able to hit their military objectives with a much lower rate of civilian casualty. This replaced using things like slide rules to calculate trajectories. War sucks, reducing civilian casualties is a basic minimum in lowering how much it sucks.

Satellite communications were also much more advanced than previous decades, making communication between troops on the ground and in the air much easier, as well as with commanders who were not in the field. Uninterrupted, clear communication can also lead to swifter resolution, and therefore to war sucking slightly less.

21st Century warfare depends on space - and on commercial providers

The second gulf war began in 2002, with an illegal invasion of Iraq by the U.S., based on what is now understood to be extremely faulty intelligence. But where intel failed at the start, satellite imagery from Earth observation satellites were key to identifying burning oil rigs and other retaliations by Iraqi troops.

Today there is no modern military that can operate without space-based capabilities for navigation, tracking the movement of adversaries, precision weapons guidance, communications, intelligence, meteorological information, planning and situational awareness on land, at sea and in the air. The eyes and ears of modern militaries are in space.

But not all militaries have access to bespoke space capabilities. This is where commercial players are becoming so critical, and the commercialisation of space has both a positive and a worrying side to it.

In February 2022, Ukraine Vice Premier Mykhailo Fedorov put out a call to the commercial space world, requesting access to Earth observation data so that Ukrainian forces could understand where attacks were taking place, and plan and respond accordingly. A number of providers answered the call and donated data for free.

Earth observation (EO) data isn’t “real time”, since satellites have to be able to pass over the specified area, gather data, then downlink this to another location where the data is processed and then provided as images. But some companies like Planet and Maxar have large enough constellations that they can provide images fairly swiftly - part of their deliberate business model. They may be lifting the fog of war by providing clarity from above.

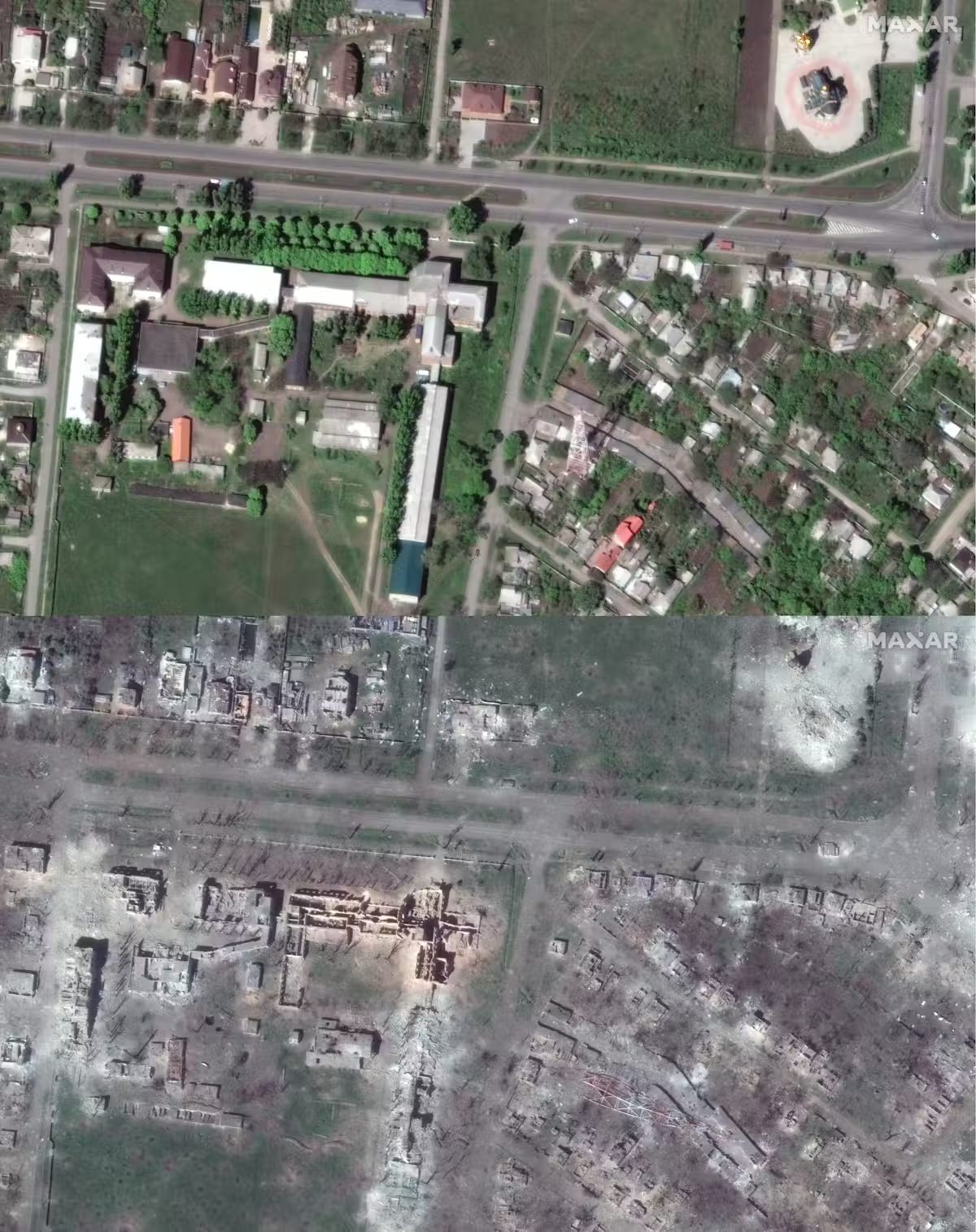

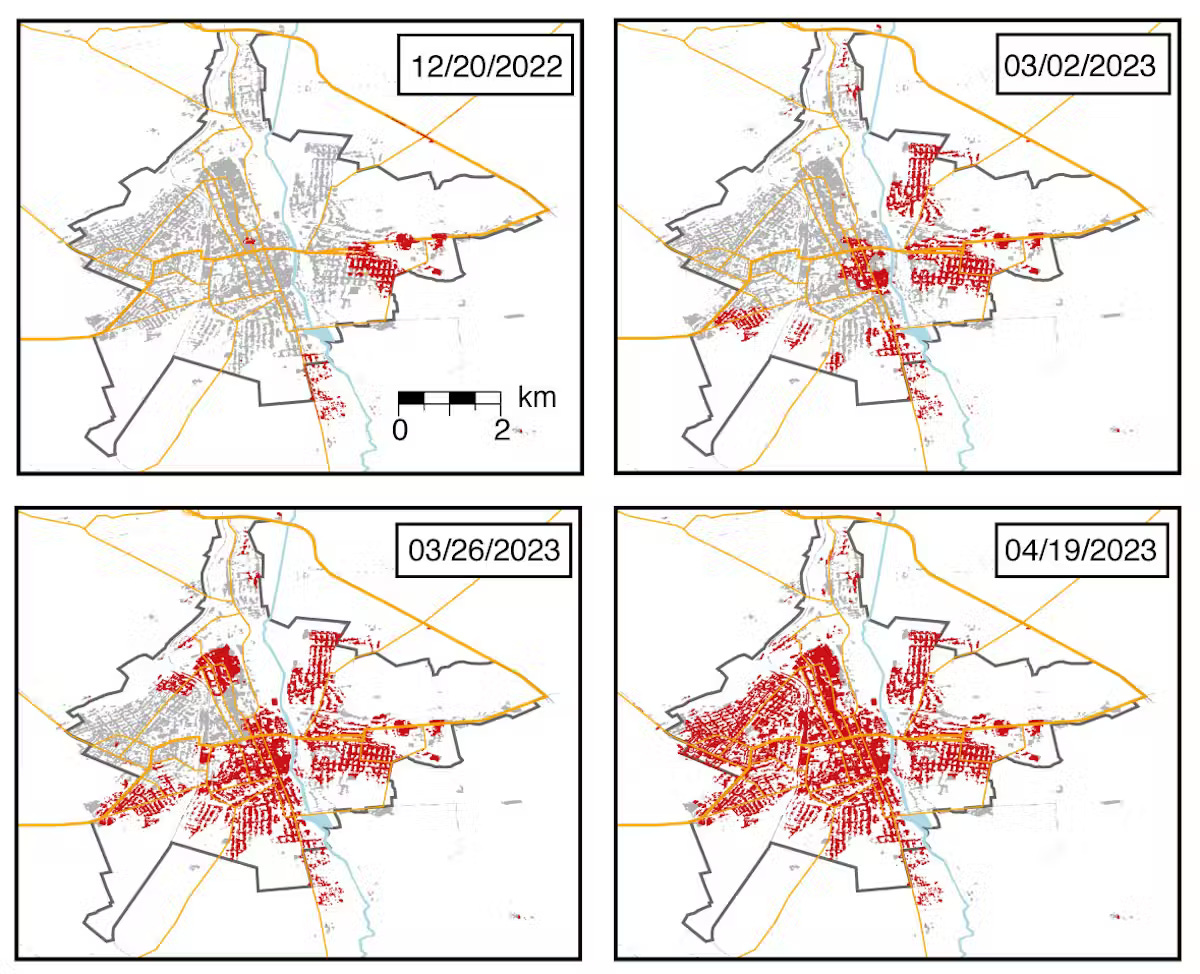

Much of this EO data has been provided directly to NATO or to the Ukraine government, but some is being made available as open source images, and provided to the media. Some researchers have been able to track urban and agricultural destruction over the past couple of years, which is both eye-opening and tragic.

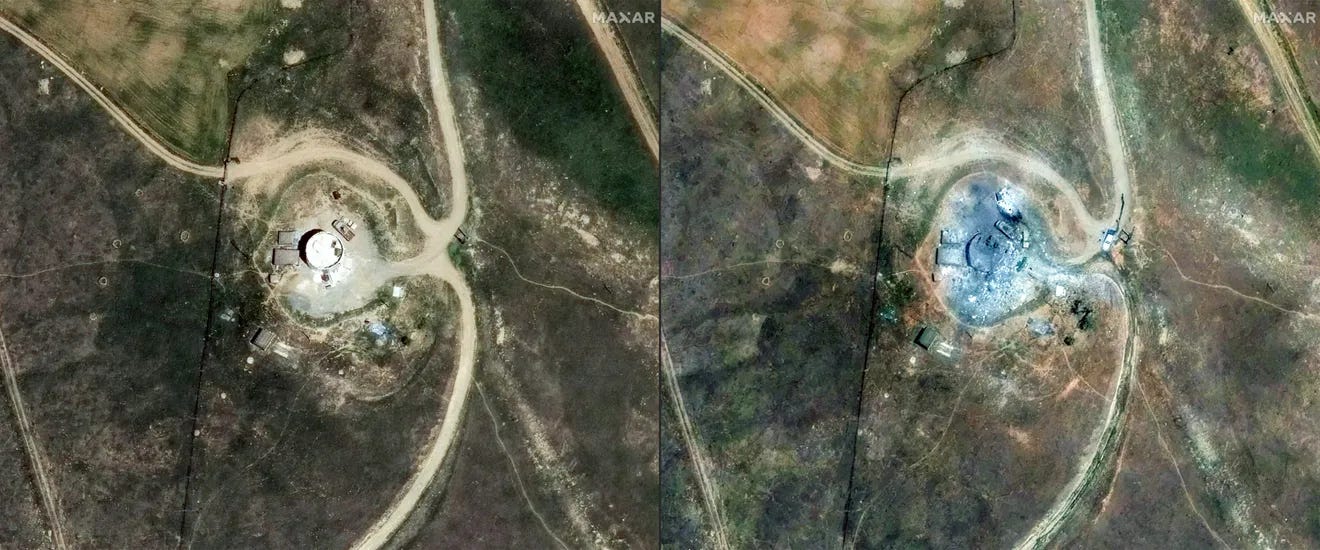

Similarly, the unlawful civilian tragedies unfolding in Gaza are made visible by EO data, including destruction of agricultural sites, and of entire housing compounds and living areas, as shown in these side by side images from October 2023 from Maxar Technologies.

On the other hand, the precision of the attacks by Israel on Iran — while also questionable as to their lawfulness — were incredibly accurate in hitting military objectives rather than civilians, thanks to intelligence gathered by EO data, and GPS-guided missiles.

Then there’s Musk (again)

Commercial providers are irreplaceable, but there is also a risk in too much dependency. You may have read about Mr Musk’s magnanimous gift of Starlink terminals to Ukrainian troops and civilians early in 2022. Musk was hailed as “saving Ukraine” for providing connectivity for free. Indeed, internet and telecommunications are critical on the battlefield, and equally critical for civilians surviving the Russian invasion.

But then, some very clever Ukrainian troops figured out how to use this connectivity signal to fly drones - a super hack - and Musk was upset that his satellite technologies had been “weaponised”, so he switched off the service.

I’ve written earlier about how fickle Musk can be, and how overwhelming his singular role in the space economy is, but the fact that he complained about the use of Starlink DURING THE CONFLICT TO WHICH HE WANTED TO PROVIDE SUPPORT for the PURPOSES OF THAT CONFLICT is baffling. The Biden government was also quite miffed, and asked him to please turn it back on. To which Musk replied sure, as long as the U.S. contracts and pays for the service with tax payers dollars.

The point is not to decry the fact that commercial space providers are intertwined with warfare - the Rubicon has been crossed on that, since the majority of all satellites today are commercially owned, and militaries purchase space services more often than they build and operate bespoke, dedicated military satellites. The point is the risk of high reliance on a single system, owned by an individual who has been utterly inconsistent as to whether he supports Russia or Ukraine, whether he sides with Israel or the Palestinians, and whose opinions on these things should not matter in the first place, but who can switch off access to this critical service at any given moment….

This is precisely why several island nations in the Asia-Pacific are considering very carefully whether they want to welcome Starlink terminals, or whether they need to hedge their bets if things get tenser in the region, and if conflict does break out. They can’t afford to lose connectivity because of one man’s shifting business and geopolitical interests.

Thankfully, SpaceX is not the only player, and satcom is not the only space capability at play.

War still sucks

…but space somehow makes it suck ever so slightly less. Precision targeting can reduce civilian losses, secure communications can keep operations shorter and more effective and keep civilians connected, satellite navigation can protect the lives of troops. A topic for another day is also how space capabilities can be used to identify mass atrocity sites and intervene in gender-based violence.

Space is an integral part of warfare. Terrestrial warfare. I emphasise that because, while space is now recognised in many military strategies and doctrines around the world as a domain of equal importance to land, sea, air and cyber, this doesn’t mean war is being fought in space. In my next newsletter I’ll say much more about what is happening in space, and why it’s so important to prevent an actual space war. Because we all depend on space so much, in war and in peace.